For the past 20 years I am the proud owner of the leading economic consulting firm in Israel. The firm specializes in real-estate development (http://www.czamanski.com/). This morning, my partner (and ex-student) published a newspaper article with a list of the failing shopping centers in Israel.

The obvious question that the article raises is why are there failures among the shopping centers? From an academic perspective, a more interesting question is whether there is order in the distribution of retail facilities. Emergence of order in complex systems is linked to the self-organization processes. Urban landscapes are often rugged and irregular, yet their distributions display a type of structure that researchers traditionally identify as order. Theories such as the central place may be considered to be descriptions of self-organization processes. One of the most commonly used examples of such order in urban systems is the rank-size rule, sometimes called Zipf's law.

Here are some graphs depicting Israel's commercial facilities system and hinting at the existence of emerging order.

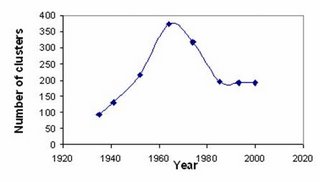

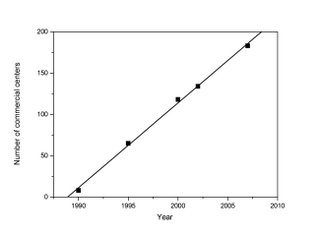

Growth in the total number of commercial centers

The obvious question that the article raises is why are there failures among the shopping centers? From an academic perspective, a more interesting question is whether there is order in the distribution of retail facilities. Emergence of order in complex systems is linked to the self-organization processes. Urban landscapes are often rugged and irregular, yet their distributions display a type of structure that researchers traditionally identify as order. Theories such as the central place may be considered to be descriptions of self-organization processes. One of the most commonly used examples of such order in urban systems is the rank-size rule, sometimes called Zipf's law.

Here are some graphs depicting Israel's commercial facilities system and hinting at the existence of emerging order.

Growth in the total number of commercial centers

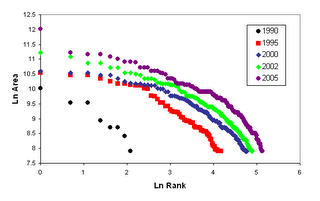

Ln Area versus Ln Rank

Ln Area versus Ln Rank

In order to test for presence of Zipf's law in the size distribution of commercial centers, we plot ln Area versus ln Rank. It is immediately clear from the above graph that the classic rank-size rule does not hold for any of the years: none of the curves can be approximated by a linear function.

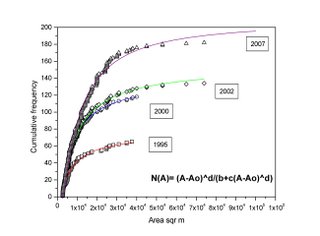

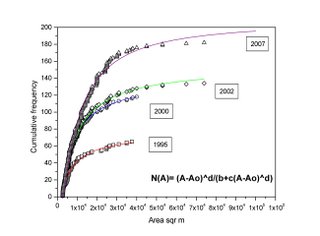

Cumulative frequencies are plotted in the following figure.

Scaling of the cumulative frequency curves

It is evident that the cumulative curves are shaped quite regularly and the deviation of the large centers from the general trend observed in rank-size graph is imperceptible in this type of presentation. A number of mild steps in the cumulative frequency curves may signify a distinction between size groups. The generally smooth shape of the curves suggests that the distribution is represented by the whole range of sizes more or less evenly and that there is no clear size groups associated with a hierarchical structure. By performing scaling it is possible to demonstrate that the frequency distribution curves for the different years do in fact follow an identical pattern.

It is evident that the cumulative curves are shaped quite regularly and the deviation of the large centers from the general trend observed in rank-size graph is imperceptible in this type of presentation. A number of mild steps in the cumulative frequency curves may signify a distinction between size groups. The generally smooth shape of the curves suggests that the distribution is represented by the whole range of sizes more or less evenly and that there is no clear size groups associated with a hierarchical structure. By performing scaling it is possible to demonstrate that the frequency distribution curves for the different years do in fact follow an identical pattern.

These graphs provide initial clues to the understanding of the structure of retail facilities in Israel. Contrary to some of the classic theories no clear hierarchy is observed in the size distribution of commercial centers. Zipf's law does not hold. However, a number of large commercial centers in the later years appear to be an exception from this law. Assuming that the self-organization processes are really taking place within the system, the large facilities may be considered "too big". A possible explanation is that their excessive sizes are a result of competitive decisions of developers, who may be prepared to incur loss in the short run, in order to insure control over a greater share of the market in future.

Cumulative frequencies are plotted in the following figure.

Scaling of the cumulative frequency curves

These graphs provide initial clues to the understanding of the structure of retail facilities in Israel. Contrary to some of the classic theories no clear hierarchy is observed in the size distribution of commercial centers. Zipf's law does not hold. However, a number of large commercial centers in the later years appear to be an exception from this law. Assuming that the self-organization processes are really taking place within the system, the large facilities may be considered "too big". A possible explanation is that their excessive sizes are a result of competitive decisions of developers, who may be prepared to incur loss in the short run, in order to insure control over a greater share of the market in future.

However, this does not seem to explain the failed facilities, inasmuch as the failures are among the smaller centers. Now I am waiting for my ex-student, Dr. Maria Marinov, to return from climbing mountains so that we can complete several papers on this topic.